#12 Exploring Agroecology through Ethnography: A 10-week inquiry into the perceptions of agroecology and positionality on the Gaudin Lab team

I had never heard of agroecology when I joined the Gaudin Lab for a summer internship on May 29, 2023. In the months before, however, I had drafted a set of learning goals and among them, hoped to define agroecology for myself and understanding its disciplinary values. As I soon found out, other members of the lab had the same goal, and they dedicated their time and care to supporting my pursuit.

I have lived in Yolo County nearly my entire life, just off a county road halfway between Winters and Woodland. Through high school, I was a student in the Davis school district. My last three years have been spent at Bowdoin College, a small liberal arts school in Maine, where I am studying Anthropology and Environmental Science. This is to say that when I joined a biophysical research lab at UC Davis to spend a summer back home, I felt simultaneously disconnected from community and reconnected to place.

Given my experience conducting interview-based ethnographic studies at school, I was encouraged by two of my PhD student mentors, Mariana Muñoz-Araya and Peter Geoghan, to design my own study with other team members at the lab. Based on conversations with these mentors and others, I chose to center the study on exploring how these researchers define agroecology and how they find themselves aspiring towards or arriving at this definition in their research. Secondly, the purpose was oriented toward identifying common interests and questions among lab members concerning the role of qualitative research methodologies in their work. The pacing of this study was driven by the timeline of my 10-week fellowship, at the end of which I presented my findings at a lab meeting, led the team through a workshop on ethnographic research methods, and facilitated a focus group discussion.

The question set for the interviews was created in conversation with members of the lab, during van rides and across lab benches. This was crucial because the data gathered in interviews needed to further develop the already ongoing discussions among lab members regarding the team’s collective research missions and stakeholders. Throughout the eight weeks of active study, I had to revisit and reevaluate this purpose of generating a collaborative, need-based assessment for the team. At various points, this meant altering the question set by turning the focus slightly away from perceptions of qualitative research and toward individualized research goals.

I conducted 25–45-minute interviews with eight members of the lab. In each conversation, I listened to the participants’ testimony with all the attentiveness I could. I understood that I was asking the interviewees to exert emotional labor and provide me with their vulnerabilities, uncertainties, and earnest questions regarding their own work. I couldn’t help but internalize what they shared as I listened back dozens of times to the recorded interviews while I weighed soil samples and biked to and from the lab. Additionally, knowing that the subjects of this study were also its primary recipients, I transcribed, coded, and analyzed the data with a particular sensitivity to the purpose of this project— that it be useful for furthering reflexive team dialogues on defining agroecology. Though I use the words participants and interviewees to describe those who contributed to this study, I must share that this language feels inadequate. It misrepresents their contribution, ordering it as data or testimony rather than capturing the truthful degree of reflexive, analytical work than was provided in each conversation.

Defining Agroecology

Each interview opened on the same question—

Could you please share your working definition of agroecology?

Within this question, I pushed participants to explain both their personal definition of agroecology and their actualized research definition.

Half of the participants shared that they had received either limited or no exposure to the scholarship of agroecology before arriving to the lab. All four articulated appreciation for the way other lab members engaged openly with their questions, reflections, and past research experiences to help them construct their own definitions of agroecology since they had joined the team. One such respondent stated,

“I was looking for the integration of ‘science’, ‘movement’, and ‘practice’, but it was only once I arrived here that I gave it words and concepts. That happened because of the peopleworking in this lab. They gave me that framework.”

This cultural dynamic at the lab helped this team member and others build more critically informed research models. These testimonies speak to the impact of reflexive, sustained dialogue among lab members concerning both personal and collective ways of defining the work. After identifying and presenting this cultural dynamic at the lab meeting, two clear follow-up questions arose during our group assessment—

Among whom and in what spaces is this type of discourse fostered? Secondly, what standards or mechanisms could be established within the team to further support the collective work of defining agroecology?

All participants openly shared their definitions of agroecology, and certain common themes emerged. All eight participants included the language of ‘science’, ‘movement’, and ‘practice’ in their definitions. Each interviewee also employed iterations of the word ‘integration’ to communicate what they perceived as the idealized purpose of agroecology; that it engenders a uniquely integrated approach to transforming contemporary food systems.Of the eight participants, five explained that their definitions of agroecology were not explicitly personal but rather functioned to frame the scope of their research. Among the three for whom agroecology did carry a personal, ideological definition, I received stories that spanned minutes of my recording rather than definitions that spanned seconds. These stories mostly centered their engagement with agroecology as a practitioner, and the learning the emerged from their relationships to land, farmers, and organizers.

Identifying dissonance

By asking the participants to next define what they perceived as a core set of agroecological principles or values, a fundamental theme of this project emerged. All members of the study shared individually that their working definition of agroecology is dissonant from their actualized research. All respondents but one shared that they do not consider their research to be agroecology. This dissonance summarizes how the type of knowledge and/or the means of creating this knowledge that is imagined in each lab member’s definition of agroecology is not reflected in or aligned with the type of knowledge or means of creating this knowledge represented in their actualized research. It’s critical to note that there is an elasticity to this dissonance. The greater the incongruence is between these components, the greater the dissonance, while the greater the alignment is between them, the greater the resonance. As such, the degree of elasticity is specific to each lab member based on their own working definitions of agroecology and perception of their actualized research. Simultaneously, their elasticity is non-static as they actively, individually negotiate new working definitions of agroecology and proceed with new frameworks for their actualized research.

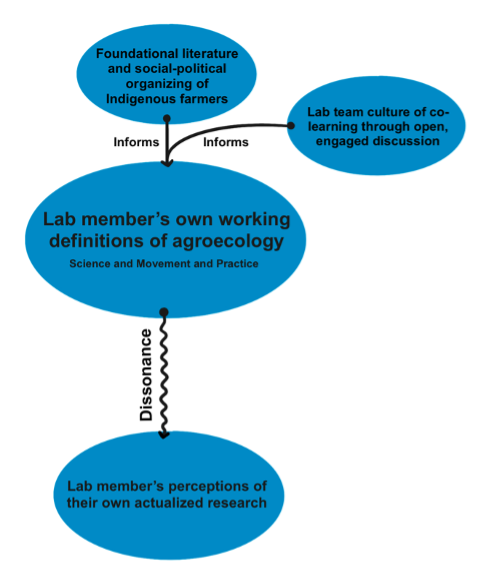

This explanatory model (Figure 1) places the dissonance in relationship with the generative sources of team member’s definitions of agroecology. The majority of participants cited foundational scholarship and the work of social-political organizers, primarily Indigenous farmers in South and Central America, as the sources that have informed their ongoing process of defining agroecology. Additionally, the lab team culture of co-learning through ongoing, open discourse critically informs the context in which this literature is shared, processed, and integrated into these working definitions. Given this model, it is critical to clarify that this dissonance does not necessarily bear an intrinsic value judgement. Rather, it identifies a shared misalignment and affords space for further discussions concerning collective definitions and research goals.

Figure 1: Dissonance model visualizing shared testimony of misalignment between the research considerations constituting lab member’s definitions of agroecology and the nature of their actualized research.

Reflexive engagement

Up through the point of identifying this dissonance with each interviewee, I perceived a notably comfortable manner of engagement with the participants— perhaps as comfortable as it ever feels to speak with someone while you scratch down notes and a conspicuous recording device lays between the two of you. Each team member seemed to speak openly and eagerly with me as they shared their definitions and the narratives behind them. I mostly felt at ease asking follow-up questions and they mostly spoke with ease in answering them.

However, this mood changed when I asked the next question in the set—

What makes someone an agroecologist?

This question seemed to generate a greater degree of uncertainty, and as such, a greater degree of discomfort expressing this uncertainty in the interview setting. In my lab team presentation, I shared that there was not consensus among lab members regarding this question. Three respondents explained independently that they imagine an agroecologist to be simultaneously engaging with the ‘science’, ‘movement’, and ‘practice’ of agroecology, and as such, to be facilitating a necessarily transdisciplinary mode knowledge creation. Two others imagined an agroecologist to be someone working on any cropping and/or livestock operation that is agroecological as an integrated system, rather than someone working on a singular agroecological management practice. Two shared a broader criterion, that agroecologists conduct research to produce or extend knowledge that could in any way transition contemporary food systems toward the types of futures imagined by the socio-political agroecology movement. One other participant explained how the ‘practice’ sits at their imagined center of what it means to be an agroecologist, and that for practitioners of agroecology, engaging with the ‘science’ and ‘movement’ is implicit.

This question above led to two others in nearly every interview—

Do you consider yourself an agroecologist, and if not, do you aspire toward this label?

Half of the respondents to the first question stated they do not consider themselves agroecologists, and among these respondents, half shared that they do aspire toward this imagined title, while the other half shared that they do not. These data must also be contextualized by the fact that seven of the eight interviewees considered their actualized research to not be agroecology. This elicits the reflection that for these participants, being an agroecologist does not necessitate doing agroecological research.

I felt compelled to present and elaborate on these data in the lab meeting because I imagined it would be perceived as the most objective and therefore most legitimate take-away. As the interviewer, however, I found myself dedicating more earnest consideration to the way lab members engaged with this question in our interviews rather than the content they shared. Social scientists often discuss a dynamic of ethnographic interviewing in which ‘words can conceal, while silences can reveal.’ The extended silences in my audio recordings during this portion indicated to me how the participants were in-process of answering these questions for themselves, and were sitting with the discomfort of me, the interviewer, bearing witness to their uncertainty. Understanding this prompted further reflection on my positionality. Despite having limited or no prior relationships with me, these lab members had the capacity and courage to gift me their vulnerable silences, uncertainties, and self-recognized contradictions. To me, this speaks to how there is space for significant uncertainty in the conversations we hold with those around us when we are able to be vulnerable and when they are able to ask informed questions and listen with care.

Reflections on my own positionality

During my final two weeks at the lab as I rehearsed the presentation and prepared for goodbyes, I found myself bothered by an element of bittersweetness to my positionality that I had not identified earlier. The following reflection was not prompted by some additional reckoning with my positionality as an undergraduate, or local resident, or even social science major at an institution across the country, but instead, simply by my positionality as the ethnographer of this study.

By conducting an ethnographic research project with the members of this biophysical research lab, I felt as if I was implicitly advocating for ethnography as a means of knowledge creation. Further even, by sharing a toolbox of ethnographic research methods in the second portion of my presentation, I was explicitly disseminating these modes of knowledge creation to this team of researchers. I felt my own sort of uncomfortable dissonance here, a dissonance between my vision for my work and my actualized research. For the most part, my studies of ethnography have shown me how very extractive and reductionistic this type of research can be. Anthropology, perhaps even more than ecology, is entrenched in historic and contemporarysystems of oppression. As a discipline, it is young in the process of admitting it’s mistakes and seems far from any significant steps of reconciliation. Since putting language to this discomfort, I’ve been asking, why did I choose to position myself as an advocate for ethnography when I am so uncertain of its place in the equitable creation or sharing of knowledge?

Simultaneously, I can recognize and owe appreciation to the stories and wisdoms that were gifted to me by the participants of this study. I do wholly believe that these sorts of reflections were shared because of the framework that semi-structured interviewing provides (informed consent, guiding question sets, reciprocal engagement, etc.). Wielding this framework, I positioned myself as the ethnographer and therefore, was perceived as a legitimate recipient of beautiful visions, vulnerabilities, and truths.

I believe I can hold the bitter and the sweet of this reflection as I move forward with my studies from here. I hope too that this project gives the team more than the document of meeting notes from my presentation or slides in the Drive. I hope there remains a more subtle residue from the experience of being subjects to an academic study; from this vantage, what worked and what did not?

I would like to first and foremost thank each member of the team that participated in this project. I must also extend an enormous thank you to Mariana and Peter for all the external support you each provided me in mentorship meetings throughout the summer, scheduled and impromptu. Thank you Amélie for your encouragement of my presentation and of this post, and to everyone who engaged with the group discussion in our meeting together; I felt your patience, grace, and support at each point along the way and this meant everything.